Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto and koto artists of last summer’s

“NextGen Geijutsuka: Future Stars of Japanese Cultural Arts” will present a special live concert featuring the koto music of Kimio Eto, arranged and performed by Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto, Brian Mitsuhiro Wong and Isabella Kazuai Lew. The concert will air on Sunday, October 25, 2020, at 4pm (pacific time) on the Old First Concert website here It will be re-broadcast on YouTube some time after the performance. For further details please go to: www.oldfirstconcerts.org.

Special note: Rare footage of Kimio Eto’s performance and interview on the Danny Kaye Show in 1966 has been just discovered. Thanks to the Danny Kaye and Sylvia Fine Foundation, we have been given permission to show a clip from this appearance only for this live performance. The re-broadcast of this concert will not be shown with this footage. Special thanks to Robert Bader for his assistance with the presentation.

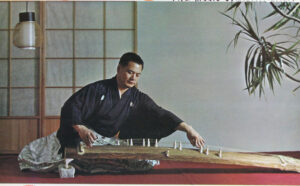

About Kimio Eto

Kimio Etō was born in Oita Prefecture on the island of Kyushu, Japan on September 28, 1924. He moved to Osaka in 1929 and lost his sight as a result of an accident at the age of five. He began studying the koto under Mamoru Tateshiro in 1933, but moved in 1934 to Tokyo, where he became apprenticed to the great composer of Japanese modern music, Michio Miyagi, who was the head of the Tokyo Music School at that time. Etō received his teaching license from Miyagi Sensei at the age of 14 in 1938. Miyagi was not one for expressing praise, but he praised the young Etō upon the completion of his teaching certification, which encouraged Kimio.

He was awarded first prize at the first Sankyoku New Works competition in 1941 for his piece entitled Duet for Koto and Shakuhachi , and second prize at the second competition in this series held in 1943 for his work Shōri no Kyoku (Piece for Victory, subsequently retitled “Piece for Hope”). His piece Kensetsu no Hibiki (Sound of Construction) won him the first prize in the third competition in this same series in 1944. He also wrote Omoide and Haru no Sugata in this same year.

In 1946, Kimio Etō married Mieko Sugiyama. One of the guests at the wedding was Michio Miyagi. In the same year, he played jazz at the US military general headquarters, a rousing version of “Bumble Boogie”, the boogie version of Rimsky-Korsokov’s “Flight of the Bumble Bee”, which was well received, but criticized by the locals. In 1952, he appeared together with the American jazz drummer Gene Krupa at the Nichigeki Theatre. That same year, he composed and performed Yuki no Gensō to provide the theme music for the movie “Nagasaki no Uta wa Wasureji “, (“I’ll never forget the songs of Nagasaki”). A year later, Etō became a member of the Friends of the Imperial Household Music Agency.

In 1953, Kimio went on a music tour from Yokohama to Hawaii at age 29. Then, he went to the mainland US, and started life in America for 12 years. He began teaching the koto in Hollywood. He gained permanent residence in the United States in 1958 and released two LPs entitled “Koto Music” and “Koto Master”, followed in 1960 by “Koto & Flute”. He gave a recital at the Ebell Theater in Los Angeles. He then moved to New York, and October 1, 1961 became the second Japanese musician to give a solo recital at Carnegie Hall. He followed this up with a recital, the first given by an Asian musician, at Lincoln Center in 1962. In 1963 he began a university support tour performing in 40 states.

In 1964, he gave the first performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Leopold Stokowski, of California composer Henry Cowell’s” Concerto for Koto and Orchestra”. He returned to Japan in 1965, where they performed the Koto and Orchestra concerto at the Nihon Budōkan in Tokyo, an arena built for sports presentations during the Tokyo Olympics (the Beatles performed there the following year). He performed the Koto Concerto with the Nippon Symphony Orchestra with guest conductor Stokowski traveling to Japan for the event. It was a great success, applauded by all involved.

For the concert at the Nihon Budōkan, he invented an 18-stringed koto because the 13-stringed koto’s sound was not loud enough to balance with the orchestra. The 18-stringed koto took on the lower bass strings of Michio Miyagi’s 17-stringed bass koto to go with the thinner strings of the traditional 13-stringed koto.

In 1967, Etō decided to return to Japan for his family. He wanted to start teaching others to carry on his music and also compose more music. He presented a commemorative concert to mark his return at the National Theatre Grand Hall in Tokyo, but there was a widening gap between the styles of contemporary Japanese music and his style of koto works. Contemporary koto music was beginning to take its rhythmic cues from western music ideas, and although Etō’s works included western ideas as well, they still had the beauty of the Japanese traditional soul. The differences in the music styles led those in Japan to steer away from Etō’s music.

He changed his stage name to Etō Kōmei in 1971 in order to note a new change in his career, and gradually reduced his major performance activities little by little, concentrating on teaching and composing. He composed some religious works, and continued to search for what he was convinced was his sound. In 1979, he became active again, resuming his presentation of his own concerts. At age 60, Etō took part in the “Japanese Traditional Culture Fair” in Nice, France in 1984. He changed his stage name back to Kimio thereafter. In 1985, he presented his 45th anniversary concert as featured artist at the National Theatre, in Japan. In 1987, he gave a “New Beginnings Concert” at the Shibuya JeanJean Theatre (a small theatre in Shibuya in Tokyo which was open from 1969 to 2000). In 1988, he traveled with Prince Tomohito of Mikasa to Norway, where he performed at an international ski tournament for the disabled. He was left semi-paralyzed by a stroke in 1995, and died from pneumonia on December 24, 2012 at the age of 88.

Kimio Etō’s three sons all inherited his love of music, and are all musicians in various fields of music. The eldest son, Hiroyuki inherited his father’s love of koto; his second son, Steve (Takato) is a percussionist, and his third son Leonard (Kozo) is still active as a Japanese taiko drummer. They are all known musicians, but why after the successes Kimio had in America and earlier in life did he become relatively forgotten?

Japanese contemporary music has continued to change and be influenced by many world influences and arts. The music of Kimio Etō was also a part of this change. There are those who wonder if, on the other hand, his music was so difficult that no one else could play it, which led to the demise of the performance of Kimio Etō’s music. Etō brought the music and culture of Japan to audiences all over the United States and the world and brought admiration of the culture with his beautiful tones.

About the Koto performers:

Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto – Koto musician, teacher, band leader, filmmaker, event producer

In 1976, Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto received her “Shihan” instructor’s license with “Yushusho” honors from the Chikushi School in Fukuoka, Japan, and her “Dai Shihan” Master’s degree from the same school. In 2012, Shirley was inducted into the Hokka Nichibei Kai Bunka (Japanese cultural) Hall of Fame, by the Japanese American Association of America. She has also been awarded grants from the Alliance for California Traditional Arts (ACTA) to train apprentices, and the Individual Artist Cultural Funding from the City of Oakland for the 25th anniversary the world jazz band she formed known as the Murasaki Ensemble. For almost 60 years, Shirley has performed and taught the Japanese koto in the Bay Area, across the U.S and in Japan, in person and on virtual platforms. Shirley has researched Japanese traditional performance arts in the World War II concentration camps, after finding out that her mother learned to play the koto from koto teachers at Topaz and Tule Lake camps. In 2012, her project was awarded a National Parks Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites grant to turn her decades-long research into a documentary film. Hidden Legacy: Japanese Traditional Performance Arts in the World War II Internment Camps which has been shown on public TV and PBS stations in the U.S. and universities here and in Japan. Hidden Legacy has recently been released for public viewing on YouTube. This past summer, Shirley produced virtual programs featuring Japanese Cultural Arts under the title NextGen Geijutsuka JCA.

Most of the music being performed in this program has not been published. For those numbers, Shirley has arranged the music based on the 4 LPs Mr. Eto produced when he was in the United States. Although they might not be just as Mr. Eto composed them, Eto Sensei always said that no one should play a piece exactly the same all the time, that one could change them as they were performed, which he actively did himself during performances.

Brian Mitsuhiro Wong, an American of Japanese and Chinese descent, won the “Grand Prix” award for achieving the highest scores on his teaching examinations from the Sawai Soukyokuin Koto Conservatory in Tokyo, Japan in July 2006, surpassing many Japanese native candidates. Brian was tested in vocal and instrumental performance, classical and contemporary koto works, shamisen, Japanese music theory and music history, sight reading, sight singing, and tuning accuracy.

In December 2019, Brian became the second koto performer (his mom was the first) from outside of Japan to qualify as a contestant in the prestigious Kenjun Koto Competition in Kurume, Japan.

Brian continues a brilliant legacy of koto performance in America that spans three generations, and has roots in the internment camps of World War II. His mother, Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto, also a koto teacher and musician, taught Brian how to play the koto from the age of 4. At the age of 16, Brian attended a concert Master Kazue Sawai. Sawai Sensei’s performance was dynamic and exciting. Brian was inspired by her performance, and decided to continue his studies at the Sawai Soukyokuin in Tokyo, Japan.

In June 2007, Brian also earned his Bachelor of Arts in Music Composition at California State University East Bay in Hayward, California. He has written works western and eastern instruments. Brian is also a jazz saxophonist. His musical mentors growing up were Khalil Shaheed and Ravi Abcarian, Dave Eshelman, Dann Zinn, Steve Parker, Michael Wirgler, Thom Kwaitkowski, his parents, grandparents and family friends.

Brian has traveled to Montreux, Umbria and Vienne Jazz Festivals in Europe with CSUEB. He has taught koto classes at UC Berkeley, and is an active composer. Brian performed at Yoshi’s Jazz Club with the Murasaki Ensemble, the CSUEB jazz ensembles, and with the Oaktown Jazz Workshop with Pete Escovedo. He has performed in concert with koto masters Kazue Sawai and Hikaru Sawai.

Isabella Kazuai Lew, an American of Japanese, Chinese, and Filipino descent, began taking koto lessons with Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto in 2005 as part of an after-school koto class program at Montclair Elementary School in Oakland. Right from the start, Isabella was an exceptional koto student, picking up techniques and songs very quickly. She continued through private lessons from Muramoto Sensei and performed at local concerts and community events, including recitals and various Cherry Blossom festivals. In 2014, Isabella was awarded funding from the ACTA Alliance for California Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program with her teacher. That same year with help from this funding, Isabella attained her Shihan teaching credentials from the Chikushi Kai Koto Conservatory in Fukuoka, Japan, and attained the professional name of “Kazuai”. Although she does not speak much Japanese, she passed her tests with flying colors because music is the universal language.

Isabella Kazuai’s curriculum included training on classical as well as classical singing, traditional, contemporary, jazz and rock music on the koto. She has written her own arrangements for koto as well. In 2020, she started assisting Muramoto Sensei in teaching the Monday Koto Workshops being taught at the Oakland Buddhist Church until the shelter in place was ordered due to the corona virus. Through studying koto, Isabella has been able to learn much about Japanese culture and hopes to help preserve Japanese traditional arts for future generations to come.

Isabella also graduated from Cal Poly at San Luis Obispo in 2019 with a degree in civil engineering.

I hope you will support these arts by joining in the viewing of this concert and continue to support our Japanese American towns, businesses and organizations during these trying times brought on by the COVID-19.

For more information, please check our website www.NextGenJCA.com.

Thank you,

Shirley Kazuyo Muramoto

Executive Producer

NextGen Geijutsuka